It Isn't the Game, It's the Gamification, Part 1

/This is the first in a two-part response to "How Video Games Are Changing Education," an infographic from Online Colleges.

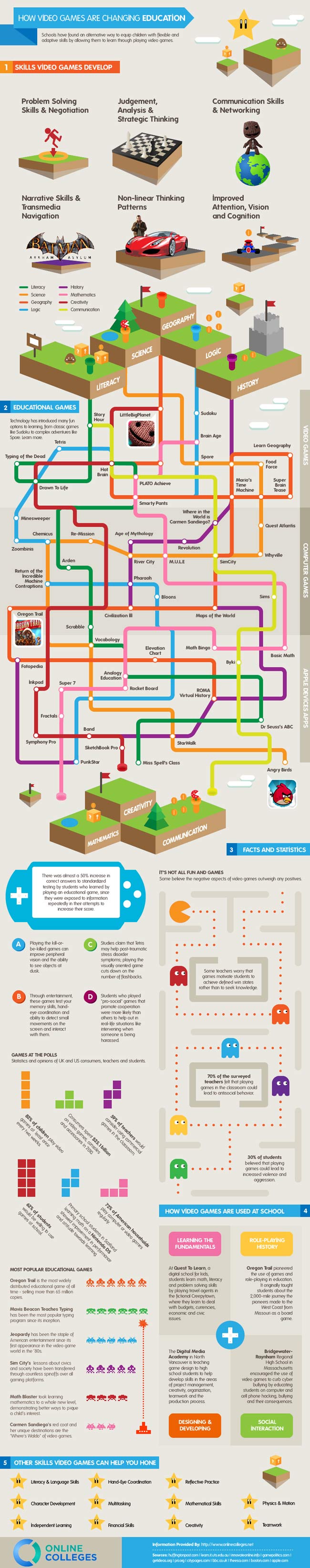

Have you seen Online Colleges' infographic about how video games are changing education before? Easy to understand, visual and accessible, it nevertheless paints only a part of the picture that should matter to someone interested in gamifying classrooms, curricula and education.

The infographic argues that video games enhance student skill development in six areas: problem solving & negotiation, judgment analysis & strategic thinking, communication skills & networking, narrative skills & transmedia navigation, non-linear thinking patterns and improved attention, vision & cognition. Some video games will certainly help learners (be they K-12 age or older...video games aren't just for kids!) in these ways, though I would argue that all sorts of games might do this, not just video games. Moreover, in some cases, non-video games would do a better job of teaching these skills than video games would. For instance, there's really no better game than "Diplomacy" to help students understand and develop their problem solving, strategic thinking and negotiation skills. But this masks a essential problem in the argument and in the development of the gamified classroom; this problem is manifested in the second section of the infographic.

Part 2 of the infographic presents dozens of video games interconnected through a complex "tube map" that suggest relationships and benefits that aren't really there. I'm not sure, for instance, how far you can reasonably push the argument that Minesweeper is a "logic" game. I love Sid Meier's Civilization series of games but the one thing they are not is a "history" game. I can offer no argument whatsoever that Sim City, another game I enjoy, is a game that develops "communication" skills. Games are never required to serve an educational purpose. When they do, however, so much the better! Minesweeper, at least nominally, can help with problem solving and judgment analysis. Civilization is a great game for developing improved attention and strategic thinking. My experience of Sim City always seemed better if I was able to break out of conventional thinking into non-linearity. But at the end of the day, this "tube map," and the facts and statistics that follow it, present more problems than solutions for educators interested in game-based learning when we discuss GBL with our colleagues and the general public.

So, what should we do?

- Focus on the Learning, Not The Games: We all agree that games are cool! We love playing them! But that doesn't mean that I as a teacher, am ever going to offer Civilization as a substitute for learning history. Ever. Rather, my responsibility as a teacher trying to gamify my classroom is to investigate how Civilization works and incorporate THAT into my classroom. How does it motivate? How does it create the flow-state that's at the heart of game-based success stories?

- Experiment Thoughtfully: I argued above that Diplomacy is a great game to help students develop their problem solving, strategic thinking and negotiation skills. A lesson about how diplomacy and diplomatic systems in Europe prior to World War I contributed to the war's beginning would definitely be enhanced by playing a few turns of Diplomacy. But it wouldn't make much sense if the game took place before students had some kind of sense of what the game was simulating.

- Believe: Ample and growing evidence strongly endorses the game-based learning approach to curriculum development, graduation requirements, classroom structure and management, student-centered learning and the creation of learning experiences. It is to these ideas that I will turn in the second part of this series.